ZYen:Long Range Finance

The following stands in for Dr Oliver Sparrow's contribution to a white board, should a meeting prove impossible to schedule.

Contents |

Resource allocation

The structural issue is not "finance", I suggest, but the mechanism and grounds for the allocation of scarce resources. Money is an example of these, but future scarcity may not be dominated by financial capital. Capital happens to have been the dominant (and most fungible) scarce resource, so markets have tended to clear around the allocation of this. (A "fungible" asset is one that can be readily exchanged or transformed into other sources of value. Cash is fungible, a Picasso painting of the same value is less so.)

Naturally, however, markets also try to clear around – or value, and make abstract - other sources of scarcity rent. These include, for example:

- Intellectual property and skills; capability networks.

- Market share and brand; "inertia" rents.

Experiments are trying to make public goods, such as clean air, fungible via emissions trading. Foreseeable tradable assets might include anything from reproduction permits to citizenship of desirable countries or city states.

Resources can be assigned in three ways: at random, by command and control or through bidding processes. Markets are the embodiment of the third of these. In a state of nature, markets barter one source of value – tomatoes – for another, for example bread. In a cash economy, barter is replaced by fungible value in the shape of money, and also in the shape of a price the universality of which is governed by information. When the pigeon was the fastest carrier of information, Rothschild made his fortune from market imperfections after the battle of Waterloo. His pigeons were fastest, and so he could handle price differences that were impenetrable to everyone else. Information technology has, of course, rendered transactions both fungible to the point of mathematical abstraction, but also made them essentially universal.

Universality has had two consequences on bubbles and instability. It has made mob sentiment global. It has pulled assets that were hitherto isolated into the sphere of speculation.

A countervailing force to universality is regulation, which has grown immensely in the past decades and which looks set to grow even faster as a result of recent events. Current markets almost always clear, at least in part, against regulatory command and control. Take the energy market: at least some future prices will be set by the state, by fiat or subsidy, in order to make renewable energy cost competitive. The state controls and allocates exploration rights in ways which seldom follow economic purism. Consequently, markets have to try to guess what state sentiment will be decades ahead. They generate assets which try to offset potential state vagaries. As the fate of industries becomes tied to political rather than economic forces, so the growth of the lobbying industry increases, and so clear economic debate becomes obfuscated by special pleading and political influence.

- "Good" regulation draws on a wide range of insight and fuses this towards a clear outcome, or a balanced set of outcomes that are deemed to be desirable: cleanliness, free competition, income redistribution and so on.

- "Bad" regulation either does not know what it wants, only what it does not want to happen, and tries to reconcile things that cannot be balanced or pursues irreconcilable objectives, such as driving for lowest cost whilst also striving to maintain levels of employment in a sector.

Regulated markets are complex, but they retain the virtue of pooling available information, and of allowing such well-constructed regulation as exists to do its work. Unhappily, markets also have the disadvantage of local rationality: that is, at this moment and in this place, people become infected by the zeitgeist and abandon analytical assessments.

Markets are innately unstable. It used to be thought that this was limited to imperfect markets – that is, those in which information was either limited or held asymmetrically; or where the behaviour of one or more dominant players could distort events (much as with state regulation, in fact.)

Imperfect information is an important concept. Agricultural price cycles dominated production for centuries until they became understood. In essence, the only signals that isolated farmers received were prices: wheat was up, chickens were down. Consequently, each independently cut investment in poultry and spent more sowing corn. This led to these being less of the one and more of the other on supply, and so prices adjusted in the opposite direction to past trends. Speculators then hoarded corn and sold "poultry futures", exacerbating the trend. Farmers reversed their former policy, creating the cycle.

Regulatory solutions to this have varied from giving farmers guaranteed prices to intervening from state storage when scarcity threatened, from episodically banning imports to setting production quotas. It turned out that the best solution was to inform farmers of the underlying trends, and let them take their own informed decisions. Cycles then vanished. Politics has prevented this approach in many countries, however.

Even with perfect information, however, markets are unstable. This is because of two forces, trading momentum and sentiment.

- Trading momentum is the term applied to the innate tendency of markets to overshoot their equilibrium point. Whatever the long run true value of an asset, if a bull market ensures that you can borrow to trade at a profit right now, then that is what it pays traders to do. The opposite is true of bear sentiment. Core groups that are cynically aware of the situation will prey on those naïve investors who believe that the prevailing trend will continue without pause. Markets transfer assets from those less able to make use of them to those with a sharper eye.

- Sentiment is an essential component of irrational behaviour. In place of analysis, "gut feeling" and the herd instinct take over. This is most evident in booms, when people believe that too much scrutiny might break the magic – "I don't know what those young guys are doing with structured investment vehicles, but gee whiz, look at those volumes!" – or when they persuade themselves that "this time it's different." The Internet boom was a good example, whereby "Internet E-conomics" was supposed to have supplanted boring old small-e economics.

Sentiment is often more subtle than this, and can have an element of truth to it. If macroeconomic systems are running smoothly, then there are grounds for generalised optimism, for example. The impact of subtle sentiment is huge and pervasive, however. Tobin's Q is a measure of market to book with the value of land factored out of it. A low Q means that if you have cash and a green field, then that is how you will choose to keep matters. A high Q means that you will build a factory on the field. We have long run data series for Tobin's Q. These show swings in sentiment that last for many years and, in some cases, for decades. People feel similarly durable sentiment that leads to expansive or cautious behaviour.

We noted three ways of allocating scarce assets: through market arbitrage, at random or by command and control. Although markets have their problems, they are usually less bad than the alternatives. Plainly, random allocation of assets cannot work except through luck, although there is evidence that some random chatter does make "sticky" markets clear better.

The third possibility is command and control. Plainly, in the hands of an omniscient being, such an approach is preferable to markets. Unlike markets, however, these do not exist. Regulators and policy makers, judges and tycoons are, from time to time, cast in the role of omniscience and some of them may briefly make a good job of it. Ultimately all will under-perform a transparent market set a clear framework against which to clear.

Risk management

To most lay people, 'risk' equates to the probability of bad things happening. When one lays off risk with insurance or prudent behaviour, one accepts a small penalty to avoid the chances of a large one. An insurance company has different aggregate risk exposure, and so can provide this service whilst also making a profit.

To the financial world, however, "risk" is not thought of primarily as the chance of bad things happening, but rather to uncertainty of outcome. There are two quite separate meanings that are bundled into this. Uncertainly may refer merely to volatility, that is, to the degree to which important aspects of a prospective attraction may fluctuate. It may also refer to asymmetrical movements in these aspects, as with a rise or decline in some value.

We need to take these in order, as they give rise to interlocking branches of a set of more or less technical instruments. Let us begin with volatility.

The promise of uncertain money tomorrow is worth less than is money in hand, with certainty, today. If you were asked to trade one position for the other, you would 'discount' the uncertain future earnings. But by how much should you discount it? Basically, your decision ought to be governed by two factors:

- By how far away in the future lies the uncertain income.

- By how uncertain – volatile – this income seems likely to be.

These two variables can be given numerical values, and brought together in a simple equation. The present value of a project equals the sum of future tranches of income, each "discounted" by a term that represents the innate uncertainty raised to the power of the time until this income arrives. Vp = Σt VfDt.

Many projects start with a period of investment (when the earnings of the period Vf are, of course, negative) and then reap their rewards. As we increase the value of D, so the immediate negatives drown out the future positives. The value of D that exactly renders the project valueless is called the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) or Earning Power (EP). It is a figure of merit of any such project, and allows projects to be ranked against each other.

By an interesting symmetry, this is also the equation which tells you how much you earn from holding an asset, where D is now the rate of interest or other value flow. Equating the two, we see that the minimal acceptable rate of return has to exceed the discount rate.

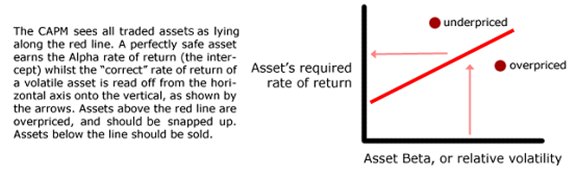

These and related thoughts get us to a fundamental relationship called the Capital Asset Pricing Model, of CAPM. This holds that any asset has an inbuilt level of uncertainty. This is generated by the environment in which it finds itself (so-called Alpha) and the asset-specific uncertainty, or Beta.

From this core idea spins off all manner of possibilities. Projects have innate volatility, which can be estimated through Monte Carlo modelling processes. That gives their required rate of return, and allows one to calculate the present value of them. The resulting rank order of capital projects provides a rational allocation of assets within an organisation. Looking at the absolute present value, or a ratio of present value to capital inputs, you pick off the most attractive of them first, and continue until the internal rate of return is equal to the cost of capital of the organisation.

What is the cost of capital? It is set by markets, and represents the cost of borrowing. As many organisations do not borrow in ways that are representative of their overall capital structure, the number can be estimated from sector Betas – as above – and the relative scale of those sectors. Any project that earns less than the overall cost of capital destroys value. Asset owners could get a better return from other projects – that is, shares and other assets – that are freely available in the marketplace. Note that the cost of capital is derived directly from volatility. If you can reduce the volatility, you can reduce the cost of capital. The threshold is lowered. Equally, discount rates fall, so IRRs improve. Consequently, the organisation can fund projects that it would otherwise have to shelve. It can attract outside assets for these projects. Consequently, reducing volatility has a direct cash value.

One can of course manage the volatility in a project. By doing so, you reduce its required rate of return, and so boost its current earnings. How is volatility to be managed in order to achieve this? You can "de-spike" a cash flow simply by borrowing. You can shift elements of parallel projects around so that the net demand for an asset is smoother than before. You can remove extremes by buying options which you exercise when things get out of the required range. All of these things are central services which the financial industry has to offer. They provide a huge element of its profitability.

Volatility equates to uncertainty, so knowledge acquires a cash value. By purchasing research, you can remove uncertainty: this is another sense of purchasing options, whereby you can cost what it is worth to spend a given sum to acquire certain knowledge.

Greater and more complex edifices can be built on this base: the Black-Scholes extension of the model underpins vast arrays of automated trading. The entire Structured Investment Vehicle debacle of the 2005-07 period is based on related concepts.

The idea can be taken too far, as any concept can burst the bounds from which it sprang. Nevertheless, almost everything that is discussed above is absolutely central to the proper working of large corporations, banks and others who manage savings. If one will need half a million dollars in the middle of next year, a service that guarantees the rate at which you buy this is obviously worth something, not least as it mitigates uncertainty and therefore reduces costs elsewhere. Machinery exists that can place exact and objective rank order on demands for scarce resources which is enormously helpful in streamlining investment decisions, in minimising office politics and in making the criteria for decision taking both transparent and related to the generation of shareholder value.

Risk and resource allocation

What is an economy? Essentially, an agreement that agents – people, companies, other bodies – will swap the fruits of specialisation.

A village community that needs shoes and wheat can either each individually sow their plots and tack their own foot wear, or specialise in being farmers and cobblers, and trade their output. Back in the Eighteenth century, Adam Smith showed how specialisation led to greater output per "factor" – unit of labour, land or capital. His contemporary Ricardo showed how exchange – that is, trade – led to all parties, even the less productive, doing better than they would without it.

Economic expansion comes from two sources. Either we increase factor flows – such as labour or capital – and output increases pro rata, or we improve the efficiency with which we use them. The latter route is discussed as changing "productivity". Specialisation has always been a source of productivity improvements, as has technology and ideas in general. Organisational capacity also increases productivity.

Competition combined with productivity drives down costs in an economy, so a given unit of output can be bargained from more. Trading against a background of increasing productivity means that all players get more than they would have had originally.

Productivity means that factors are used more effectively, and if it grows faster than does output, then factors will be released. That is, firms will generate profits that they do not reinvest, and they will shed workers. New industries will absorb these workers if they have the required skills to be cost effective, and – in a state of nature – their wage will adjust to reflect this. In a modern economy, they may prefer not to work and survive on welfare if the wage – that is, the value that they are able to add - is too low. Industrial economies survive this by drawing on the skills of lower wage economies.

These forces do not absolutely require an abstract financial system. Barter has its limits, however, and money appeared about six thousand years ago. It acts as both a fungible token and a store of wealth. It sits alongside other forms of wealth, such as military strength, personal reputation and technological insight. When financial markets trade they are, however, dealing with barter in a fungible form. They still swap shoes for wheat, but in a form where these commodities have been blended together into an abstract token.

At bottom, however, two things are going on in any financial market:

- Barter between different kinds of surplus and the need for these. "Surplus and need" can refer to savings and investment opportunities, or to real goods and necessities, such as wheat and hunger.

- Provision of services that allow the management of scarce resources to be handled effectively, as discussed in the preceding section.

The figures of merit for these activities relate to the following:

- The unit cost of any such transaction.

- The potential universality of the transaction – asking whether it is known and acted upon all those who might have an interest in it, for example.

- To its long-run efficacy in matching resources with needs that make best use of them. Here, the word "best" has a very specific meaning, relating the discounted net present value of the resulting earnings stream.

Where does this simple approach fail to satisfy? Final consumption has a different sense of "best". A starving person may gain more utility from a loaf than someone who has to break it up for the birds. The economic engine does not 'give according to need' but entirely according to the scale of latent profit.

The role of profit

The entire economic engine runs on the basis that each of us has to produce in order to consume. If we do not generate a surplus – if the cost of our livelihood is not less than the consumption that we need in order to run our lives - then (without state or charitable intervention) we will gradually see our activities draw to a halt. Profit – an economic surplus – is required if the engine is to keep turning. Gross National Product measures the aggregate sum of such added value.

At the level of the individual agent, profit maximisation drives productivity, which in turn drives growth. In the foreseeable world of nine billion people and universally scarce resources, we will need to increase our efficiency many fold. Profit is also the motive of many innovators and entrepreneurs – who may also work for reasons of creative satisfaction and other drives – but for whom profit is always a consideration.

Profit is not, however, a goal which a society can afford to pursue without regulatory moderation. The reason is that competition has powerful positive feedback, in that the successful tend to consume or destroy the less able. Dominant agents have five undesirable features:

- Their costs tend to be high, and they have no motive to lower them. Goods, therefore, tend to be costly.

- Their profit margins are arbitrary and usually high, also making goods more costly than they need to be.

- They have no motive to innovate, and oppose new entrants with new ideas.

- Their power can cause them to act callously to their employees, to customers and to the environment. They often acquire a sense of entitlement and may act in ways which provoke corruption.

- In that they are not improving their efficiency, they are not generating and recycling in to the economy the surplus factors that would otherwise be expected, as discussed above.

The issue of industrial costs has a further ramification. Industry profit is defined by the marginal cost curve. That is, the price is set by the marginal seller – the agent who is just covering production costs.

As already noted, if there is only one agent, the selling price becomes arbitrary, for lack of competition. If there is a dominant player, their costs may be so much lower than anyone else's that they siphon off nearly all the profit, and thereby further increase their relative strength in the market.

At the other extreme, however, a commodity is a good that is produced by many agents with very similar cost positions. In this case, the price falls to near the universal marginal cost of production, and no organisation makes a return that will meet their cost of capital, or which will attract further investment. Peasant farmers are often found in this situation, which offers no easy exit strategy.

Policy measures against market concentration – monopoly law, measures to curb unfair competition and so forth - are commonplace. Commodity producers are, however, extremely useful to the rest of the economy – providing food at a very low price, for example – and many states prefer to transfer latent instability into the countryside, where it is easier to manage than a restive and costly urban work force.

Arguments against a focus on profit tend to bounce off the sealed carapace of economics, as so far explored. One may assert that goods should be provided to the most needy, not those most able to pay. It is not at all clear how such a structure could be expected to work, save through command and control. So, it followed that command and control was what the Communist world installed, and it suffered greatly thereby. Nevertheless, it did work for half a century and provided a modest standard of living. Markets are not indispensable, merely the best tool that we have at the present time.

Looking forward

Markets trade completely fungible instruments, easily defined commodities and – at the opposite extreme – unique items such as antiques, art works and property. There is no reason to suppose that they could not trade other sources of value, such as skills, access to knowledge networks, intellectual property and regulatory permissions.

Indeed, anything that the law does not put beyond trading can be traded, and markets will exist for it. Even back in the pre-Internet days of Mintel, services rose dominated online commerce in France. Anyone who types "sex" into Google today will see how far and how wide this particular branch of commerce has expanded in ten years.

It is for regulators to say what else markets can or should trade, and it is their decision as to how much they choose to complicate existing commerce by adding additional factors against which markets must clear. The impact of pensions liabilities on corporate values is a good example of how regulation has utterly altered the analyst's landscape.

However, environmental goods are becoming an essential part of any cost structure. They may well become tradable amongst consumers as well: for example, anything from a birth right, a work permit to air miles – that is, individual permission to consume these – may be sold when such things become rationed.

What additional services might the financial services community offer to the world? It is fair to say that risk bundling and trading is unlikely to reach the levels that we have seen in the past. Investment banking has probably hit its peak. Private equity – hand-holding by investors of the management team - and focused venture capital still have a long way to go.

Retail banking may re-invent itself. At present, small scale capital is not seen or traded by the main markets. Les than ten percent of trade volumes go to the ninety percent of private and quoted US book value that lie outside of the top 500 organisations. Information technology and better – that is, automated and compatible – accounting systems may bring capital more easily and more securely to entrepreneur and others who need it, rather than to the big fish who have much less profitable use for it. They appear safe, and the minnows do not; but a well-understood minnow is safer than a shark.

Insurance is, on the whole, set to decline. It is often based on almost pre-industrial practices, most of which are being modernised by information technology and modelling. As new systems replace the obscure – some would say obscurantist – structures that allowed these companies to stick to so much of their turnover, so that proportion will fall. The retail banking industry retains around 2-3% of turnover; insurance up to ten times that. Insurance represents around 6% of the OECD gross product as a result.

One contribution may come from the insurance industry, however, whereby risk is reduced by the active involvement of assessment teams. That is, if you want cover for an oil rig, you must accept the insurer's team on site, and comply with their recommendations around plant and process. A bank that offered to trim 2% off a company's cost of capital would be a welcomed service. Private equity or venture capital which held hands even more than is currently fashionable would enjoy good returns if it could find the relevant 'serial entrepreneur' staff, who are currently scarce.

That said, it remains a fact that assets need to be allocated to those who have the very best – or at least, a good - use for them. A balance has to be struck between investment and consumption. Investment must be properly guided by rational principles that relate to its efficiency in doing its task.

These tasks come in five forms:

- We invest to replace depreciated or no longer useful facilities.

- We invest to increase output.

- We invest to achieve new capabilities, including increased efficiency.

- We invest in things which will have an indirect bearing on future economic efficiency – communications, transport, security, a healthy and educated work force.

- As something between consumption and investment, we spend on things which make for a more pleasant society. These range from public amenities to social engineering. Politicians who favour them call them "investment". It may well be that a market mechanism by which the public assigned funds to rival projects would generate a batter outcome than does current whimsy and populism.

With the exception of the last, only markets are able to perform a good service. They must be overseen and regulated, but it is difficult to envisage an alternative. Experiments such as the person-to-person funding sites on the Internet have not been a major success, and it is hard to see what they do that a retail bank does not.

Looking forward, however, it may be that technologies such as those outlined in the 2040 Scenarios in the Waking Up case will have much to say to this. A collectively aware structure with settled values would indeed supplant much of the financial system. And the political system. And conventional management. And…

Related articles

McKinsey Quarterly, "What's Next for Global Banks?", March 2010

World Economic Forum, "The Future of the Global Financial System"